There are Bank Reserves, but not for all

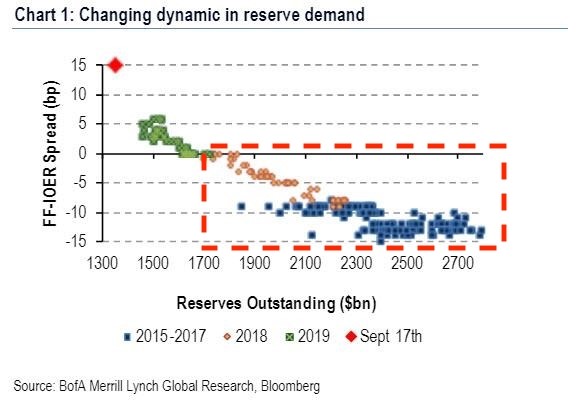

The jump in short-term funding costs in the US last month and subsequent liquidity injections from the Fed through emergency repos fueled debates about a new round of QE. Asset purchases will increase the level of bank reserves, but what should be the size and duration of the operation? One of the simple charts that I posted earlier indicate that the control over market interest rate is secured with reserves exceeding 1.7 trillion. dollars:

Recall that in the current “abundant reserves” system of interest rate control (we talk about federal funds rate, FF), the upper limit of the corridor is the excess reserves interest rate. This is the interest rate that the Fed pays on banks’ deposits (reserves). The difference FF - IOER should usually stay below or at 0, since positive value means the market rate gets out of the Fed’s control. On the chart above, the area highlighted in dashed lines is the reserves interval at which this spread was below 0.

So, does the Fed need to make QE worth at least $350-400B to bring the FF back to control? An examination of post-crisis regulation of banks suggests that the required size of asset purchases may be even greater.

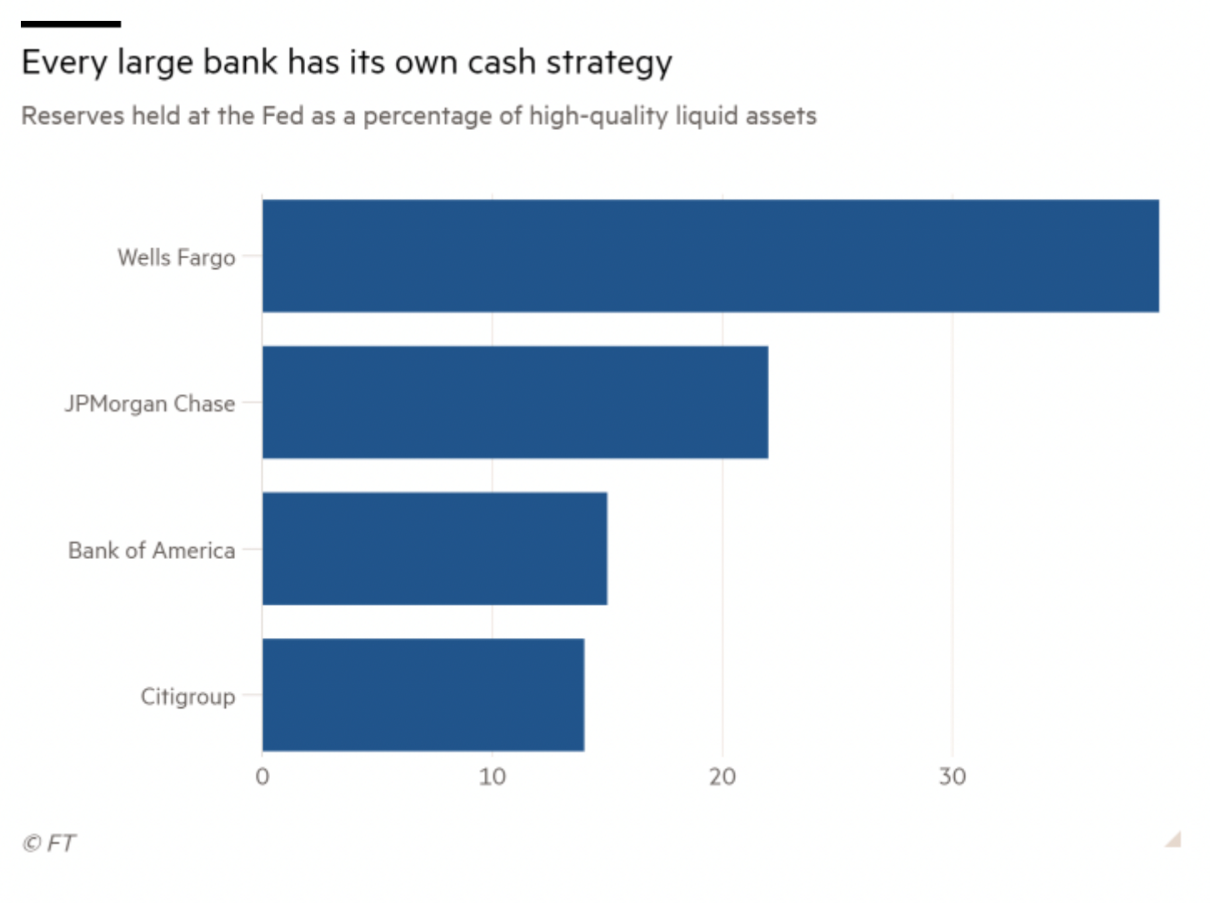

As I noted earlier, one more factor hindering the adjustment of supply to demand spikes in the money market is the concentration of banks' reserves. One of the reasons for this was the tightening of liquidity requirements (especially one-day) for large banks. One-day liquidity requirements concerns particularly cash reserves, i.e. the most liquid asset. Large banks can "sit" on huge reserves, while smaller market participants can frantically search to borrow from somewhere, pushing the market rate up. Reserves seem to be there, but the banks can be unable or unwilling to lend them.

According to the Fed research, reserves-to-assets ratio of the 25 largest US banks is 8% on average, compared to 6% for other banks. The “appetite” for reserves is even more disproportionate within the top 25 - the aggregate reserves of JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup and Wells Fargo (Big 4) rose to $ 377 billion at the end of the second quarter, which is significantly more than for the remaining 21 banks.

The post-crisis era of regulation was accompanied not only by an increase in liquidity coverage ratios (LCO), but also by an increase in the share of one-day liquidity (reserves) in highly liquid assets. The liquidity requirement may vary depending on the business model of banks, types of services and operations, which puts an extra premium for required reserves:

A recent NY Fed survey showed that the level reserves which is comfortable for the US banking system should be somewhere between $ 800-900 billion. But recent occurencies in the repo market tell something different – concentration of reserves and unforeseen demand make even the current $1.350 trillion too low.

Please note that this material is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice.

Disclaimer: The material provided is for information purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice. The views, information, or opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author, and not to the author’s employer, organization, committee or other group or individual or company.

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

High Risk Warning: CFDs are complex instruments and come with a high risk of losing money rapidly due to leverage. 72% and 73% of retail investor accounts lose money when trading CFDs with Tickmill UK Ltd and Tickmill Europe Ltd respectively. You should consider whether you understand how CFDs work and whether you can afford to take the high risk of losing your money.

Futures and Options: Trading futures and options on margin carries a high degree of risk and may result in losses exceeding your initial investment. These products are not suitable for all investors. Ensure you fully understand the risks and take appropriate care to manage your risk.